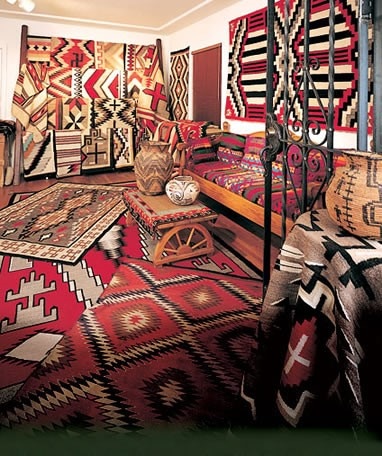

Navajo Rugs & Blankets

According to Navajo legend, Navajo women were taught weaving by Spider Woman, whose home is Spider Rock in northeastern Arizona Canyon de Chelly. The legend of Spider Woman is a favorite of Navajo weavers, but evidence points to the fact that the Navajos actually learned weaving from the Pueblo Indians. Pueblo peoples had been raising cotton and weaving it into cloth on upright looms since 1100 A.D.

Shop for Rugs and Blankets

The Spanish Influence

When the Spanish arrived in the Southwest from Mexico in the sixteenth century, they brought churro sheep and introduced the concept of weaving their wool into cloth.

Oppressive Spanish rule caused the Pueblo Indians to leave their villages along the Rio Grande River in New Mexico, fleeing west to find refuge among the Navajos. As a result, the Navajos were able to observe and learn Pueblo weaving techniques.

Unlike the Pueblos, where men were the weavers, women became the weavers in the Navajo culture. Martin Link, Former curator of the Navajo Tribal Museum explains:

"Pueblo men were the cultivators of cotton, and it seemed proper that they should utilize the product of their labor. When Navajos obtained sheep, the men probably considered it beneath their dignity to sit around all day and take care of a flock of tame animals. So the sheep were given to the women and children for care.

Gradually the women came to own the sheep. It followed that if women owned the animals, they owned the wool. So to a great extent the women became Navajo weavers.

Discovering the Advantage of Wool

Originally, the Navajos wove utilitarian items of clothing such as blankets, mantas, and belts for their own use and for trade with other Indian groups. Early Navajo blankets were used as outer garments for protection from the elements.

Tightly woven of wool, they provided warmth and because of the oil in the wool also shed water. Although generally woven on the loom in a longer than wide rectangular shape, Navajo blankets were worn in exactly the opposite orientation, with the width across the shoulders and the ends joined in front.

One of the most widely recognized blanket types to emerge during this period was the so called chief style, a specific type of man's blanket. These blankets were rare and valuable trade goods, especially popular among the Plains Indians and Utes of the Great Basin.

The Right Pattern

Like the Pueblo wearing blanket from which it evolved, the Navajo chief blanket was distinctively patterned in broad black, indigo and white horizontal bands. It was later modified to incorporate red and orange wools along with diamonds, boxes, crosses and stripes in the design.

Weavers augmented the natural white and brown colors of the wool with navy blue and vivid reds brought by the Spanish. The blue was obtained from indigo plant dye, and the red from commercially woven bolts of cloth called Bayeta.

Bayeta's scarlet to crimson color came from the dye, cochineal, extracted from dried, crushed insects native to Mexico. The Navajos tediously unraveled the cloth, strand by strand, then twisted together several plies and rewove the yarn into their own textiles. They did the same with bolts of American flannel, when it was available.

Its not unlikely that unraveled strands from red flannel long johns also found their way into some early Navajo weavings.

Evolving Designs & Techniques

The Navajos eventually learned to make natural dyes for their wool. Through trial and error they produced a range of colors using dyes made from a variety of local roots, plants, flowers, fruits, berries, nutshells, the leaves and bark of trees, even dried insects. Today, in remote areas of the reservation, some Navajo weavers still dye their wool using the same age old process.

In the late 1800s the railroad came to Navajo country, connecting isolated Indian settlements with the big cities to the east and west. White traders also came, setting up trading posts across the reservation that offered clothing, cooking utensils, hardware, grains, processed food and, not least of all, Pendleton blankets.

Colorful and inexpensive, the Pendletons had particular appeal to Navajo women who might spend half a year weaving a wearing blanket of similar size.

The art of weaving might have perished but for the traders, who urged the women to turn from weaving blankets to weaving rugs for the Anglo Tourists who were coming to the area by the trainloads seeking Navajo handcrafts. The traders provided the weavers with new weaving materials and design ideas and helped them establish a new market for Navajo rugs.

To accommodate the tastes of non Indian buyers, the rugs were embellished with new patterns contained within borders. Many of the new designs were actually suggested by the traders; others were inspired by motifs found in Oriental carpets.

Shortly after the turn of the twentieth century Navajo rugs began to be identified by geographic origin, with the trader again playing a role. The various designs and types became standardized around trading posts. Ganado and Crystal were the earliest, then Chinle, Wide Ruins, Two Grey Hill, Teec Nos Pos, Klagetoh and others.

Not all rugs were tied to a region on the reservation, but the trend was strong and, to some extent, continues today, fueled by the appreciation of buyers and the neighborhood pride of the Navajo weavers.

Shop for Rugs and Blankets

The Spanish Influence

When the Spanish arrived in the Southwest from Mexico in the sixteenth century, they brought churro sheep and introduced the concept of weaving their wool into cloth.

Oppressive Spanish rule caused the Pueblo Indians to leave their villages along the Rio Grande River in New Mexico, fleeing west to find refuge among the Navajos. As a result, the Navajos were able to observe and learn Pueblo weaving techniques.

Unlike the Pueblos, where men were the weavers, women became the weavers in the Navajo culture. Martin Link, Former curator of the Navajo Tribal Museum explains:

"Pueblo men were the cultivators of cotton, and it seemed proper that they should utilize the product of their labor. When Navajos obtained sheep, the men probably considered it beneath their dignity to sit around all day and take care of a flock of tame animals. So the sheep were given to the women and children for care.

Gradually the women came to own the sheep. It followed that if women owned the animals, they owned the wool. So to a great extent the women became Navajo weavers.

Discovering the Advantage of Wool

Originally, the Navajos wove utilitarian items of clothing such as blankets, mantas, and belts for their own use and for trade with other Indian groups. Early Navajo blankets were used as outer garments for protection from the elements.

Tightly woven of wool, they provided warmth and because of the oil in the wool also shed water. Although generally woven on the loom in a longer than wide rectangular shape, Navajo blankets were worn in exactly the opposite orientation, with the width across the shoulders and the ends joined in front.

One of the most widely recognized blanket types to emerge during this period was the so called chief style, a specific type of man's blanket. These blankets were rare and valuable trade goods, especially popular among the Plains Indians and Utes of the Great Basin.

The Right Pattern

Like the Pueblo wearing blanket from which it evolved, the Navajo chief blanket was distinctively patterned in broad black, indigo and white horizontal bands. It was later modified to incorporate red and orange wools along with diamonds, boxes, crosses and stripes in the design.

Weavers augmented the natural white and brown colors of the wool with navy blue and vivid reds brought by the Spanish. The blue was obtained from indigo plant dye, and the red from commercially woven bolts of cloth called Bayeta.

Bayeta's scarlet to crimson color came from the dye, cochineal, extracted from dried, crushed insects native to Mexico. The Navajos tediously unraveled the cloth, strand by strand, then twisted together several plies and rewove the yarn into their own textiles. They did the same with bolts of American flannel, when it was available.

Its not unlikely that unraveled strands from red flannel long johns also found their way into some early Navajo weavings.

Evolving Designs & Techniques

The Navajos eventually learned to make natural dyes for their wool. Through trial and error they produced a range of colors using dyes made from a variety of local roots, plants, flowers, fruits, berries, nutshells, the leaves and bark of trees, even dried insects. Today, in remote areas of the reservation, some Navajo weavers still dye their wool using the same age old process.

In the late 1800s the railroad came to Navajo country, connecting isolated Indian settlements with the big cities to the east and west. White traders also came, setting up trading posts across the reservation that offered clothing, cooking utensils, hardware, grains, processed food and, not least of all, Pendleton blankets.

Colorful and inexpensive, the Pendletons had particular appeal to Navajo women who might spend half a year weaving a wearing blanket of similar size.

The art of weaving might have perished but for the traders, who urged the women to turn from weaving blankets to weaving rugs for the Anglo Tourists who were coming to the area by the trainloads seeking Navajo handcrafts. The traders provided the weavers with new weaving materials and design ideas and helped them establish a new market for Navajo rugs.

To accommodate the tastes of non Indian buyers, the rugs were embellished with new patterns contained within borders. Many of the new designs were actually suggested by the traders; others were inspired by motifs found in Oriental carpets.

Shortly after the turn of the twentieth century Navajo rugs began to be identified by geographic origin, with the trader again playing a role. The various designs and types became standardized around trading posts. Ganado and Crystal were the earliest, then Chinle, Wide Ruins, Two Grey Hill, Teec Nos Pos, Klagetoh and others.

Not all rugs were tied to a region on the reservation, but the trend was strong and, to some extent, continues today, fueled by the appreciation of buyers and the neighborhood pride of the Navajo weavers.