A History of Pueblo Pot Making

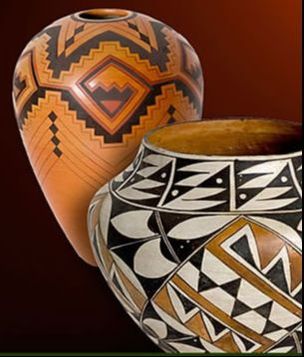

Few objects made by Native Americans have received as much attention as the pottery of Southwestern Pueblo Indians. With a background of skills developed over many hundreds of years, Pueblo potters have succeeded in producing an enviable record of artistic achievement.

Shop for Pottery

They have attained an excellence in form and design comparable to that seen in pottery made throughout the world, even though they work without the aid of such mechanical devices as the potter's wheel or the molds. Economics, trade, the importance of social identity, and pride of heritage have sustained these artistic traditions.

Revivals of the art, reinstatements of earlier ceramic styles, and its continuation by younger generations of Puebloans have been encouraged by the imagination and innovation of the potters themselves as well as by the patronage of museums, foundations, and individual collectors.

Passing On The Skills

The technology of pottery making is generally passed from older to younger women. Perhaps because it was a woman's art, perhaps because it was an Indian art, or perhaps for other reasons, Pueblo pottery was largely an anonymous art.

Except for the last fifty years or so when potters began to sign their work, we have little or no information regarding the makers of most of the vessels and know very little about the potter's own view of her art.

While early pottery may seem to us an anonymous art, to Pueblo women it was very much a known art. Within a given village, everyone knew the other's work. They had to, if only to be able to retrieve their own vessels from a group of food or beverage containers at a communal gathering.

Obviously, Pueblo pottery was functional. Yet even utility pieces were more than that. Many pueblo potters believe that they do not just make pots, they create living things, and there is much more to the clay they mold than mud. They refer to the clay as Mother Earth, which speaks to them as they work, telling them the shapes and forms their pottery will take. The result is not just a pot but also an extension of their being, of their innermost feelings.

The Tradition Continues

The Pueblo peoples' reverence for their cultural heritage has played a significant role in the development of contemporary pottery. The Hopi potter, Nampeyo, Maria Martinez of San Ildefonso, and Margaret Tafoya of Santa Clara were among the first to make use of ancient pottery styles and designs in their work. Their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren continue this tradition today.

But there are many other families of potters that have followed the same path the Lewis and Chino families at Acoma, the Medina family at Zia, the Herrera family at Cochiti, the Kalestewa and Paynetsa families at Zuni, the Tenorio family at Santo Domingo, the Chavarria family at Santa Clara, Gladys Paquin and her family at Laguna. The list goes on and on.

Shop for Pottery

They have attained an excellence in form and design comparable to that seen in pottery made throughout the world, even though they work without the aid of such mechanical devices as the potter's wheel or the molds. Economics, trade, the importance of social identity, and pride of heritage have sustained these artistic traditions.

Revivals of the art, reinstatements of earlier ceramic styles, and its continuation by younger generations of Puebloans have been encouraged by the imagination and innovation of the potters themselves as well as by the patronage of museums, foundations, and individual collectors.

Passing On The Skills

The technology of pottery making is generally passed from older to younger women. Perhaps because it was a woman's art, perhaps because it was an Indian art, or perhaps for other reasons, Pueblo pottery was largely an anonymous art.

Except for the last fifty years or so when potters began to sign their work, we have little or no information regarding the makers of most of the vessels and know very little about the potter's own view of her art.

While early pottery may seem to us an anonymous art, to Pueblo women it was very much a known art. Within a given village, everyone knew the other's work. They had to, if only to be able to retrieve their own vessels from a group of food or beverage containers at a communal gathering.

Obviously, Pueblo pottery was functional. Yet even utility pieces were more than that. Many pueblo potters believe that they do not just make pots, they create living things, and there is much more to the clay they mold than mud. They refer to the clay as Mother Earth, which speaks to them as they work, telling them the shapes and forms their pottery will take. The result is not just a pot but also an extension of their being, of their innermost feelings.

The Tradition Continues

The Pueblo peoples' reverence for their cultural heritage has played a significant role in the development of contemporary pottery. The Hopi potter, Nampeyo, Maria Martinez of San Ildefonso, and Margaret Tafoya of Santa Clara were among the first to make use of ancient pottery styles and designs in their work. Their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren continue this tradition today.

But there are many other families of potters that have followed the same path the Lewis and Chino families at Acoma, the Medina family at Zia, the Herrera family at Cochiti, the Kalestewa and Paynetsa families at Zuni, the Tenorio family at Santo Domingo, the Chavarria family at Santa Clara, Gladys Paquin and her family at Laguna. The list goes on and on.